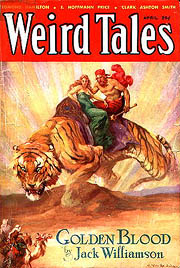

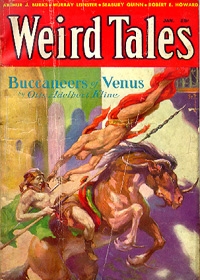

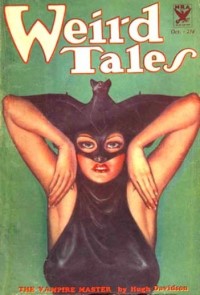

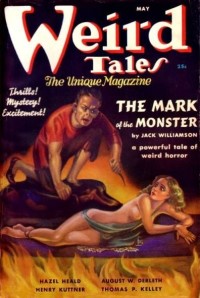

J.C. Henneberger began Weird Tales in March of 1923 "to give the writer free rein to express his innermost feelings in a manner befitting great literature," he later said. From the beginning, it was clear that the magazine existed in its own abyss, an outsider, unlike anything before or since. Poets and authors who favored the darker side, dream-spinners and troubled souls seeking an outlet, found one in its pages.

J.C. Henneberger began Weird Tales in March of 1923 "to give the writer free rein to express his innermost feelings in a manner befitting great literature," he later said. From the beginning, it was clear that the magazine existed in its own abyss, an outsider, unlike anything before or since. Poets and authors who favored the darker side, dream-spinners and troubled souls seeking an outlet, found one in its pages.

Henneberger, a journalist who had steeped himself in the dark, southern fantasies of Poe for much of his life, began by hiring well-known Chicago author Edwin Baird to serve as Weird Tales’ editor, assisted by Farnsworth Wright and Otis Adelbert Kline.

The pulp, called such because of the cheap pulpwood paper it and other lower-priced magazines of the day were printed on, struggled under Baird’s editorship. Stories were uneven, and chiefly uninspired. Still, the occasional masterpiece crept through, such as Anthony M. Rud’s tense psychological study, "A Square of Canvas," or Herbert J. Mangham’s "The Basket," which critic and anthologist Marvin Kaye compares to the existential vignettes of Albert Camus.

The Dark, Baroque Prince

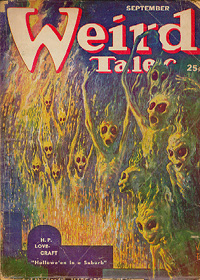

Perhaps the greatest discovery under Baird’s editorship was a man whom author Stephen King calls, "Weird Tales’ dark, baroque prince," the statuesque visionary, H.P. Lovecraft. Afflicted with health  problems for much of his younger life, Lovecraft spent most of his years secluded in his Providence, R.I., home with his two aunts, reading dusty tomes from his grandfather’s library and scribbling dark tales of cosmic horror. Lovecraft is most famous for creating what would later be called the Cthulhu Mythos, a cadre of indescribably horrific beings, sometimes called the Old Ones, who inhabit the dark infinity outside mankind’s feeble perception. In these stories, Lovecraft also created the forbidden Necronomicon, an ancient and dangerous grimoire of treacherous lore which must never be looked upon by mortal eyes. Lovecraft encouraged other authors to use his creations and supply their own additions, a literary game which elevated the mythology to a level of verisimilitude where many readers believed it to be a genuine theology.

problems for much of his younger life, Lovecraft spent most of his years secluded in his Providence, R.I., home with his two aunts, reading dusty tomes from his grandfather’s library and scribbling dark tales of cosmic horror. Lovecraft is most famous for creating what would later be called the Cthulhu Mythos, a cadre of indescribably horrific beings, sometimes called the Old Ones, who inhabit the dark infinity outside mankind’s feeble perception. In these stories, Lovecraft also created the forbidden Necronomicon, an ancient and dangerous grimoire of treacherous lore which must never be looked upon by mortal eyes. Lovecraft encouraged other authors to use his creations and supply their own additions, a literary game which elevated the mythology to a level of verisimilitude where many readers believed it to be a genuine theology.

While Baird purchased almost everything Lovecraft submitted, Henneberger has claimed that Baird disliked Lovecraft’s fiction and only purchased the stories under Henneberger’s orders. Baird’s rejection of similarly promising material (such as Greye La Spina’s classic, "Invaders from the Dark") would seem to bear this out. According to author E. Hoffmann Price, "Baird was an idea man. Once the idea was going, he swiftly lost interest in it."

The Golden Age

After 14 issues of uneven quality, Henneberger replaced Baird with Farnsworth Wright, who until then had served as the pulp’s chief r eader of manuscripts. With Wright, a tall, gaunt man afflicted with Parkinson’s Disease, Weird Tales found its cloven hoofs, and The Unique Magazine began to publish some of the finest, and strangest, fiction ever marketed to a popular audience. The time was the mid-1920s, and Weird Tales’ cadre of poets and authors, led--artistically at least--by Lovecraft, told of a dark, surreal world of cyclopean horror which ran anathema to the Jazz Age of gin, speakeasies, and beautiful flapper girls. "For Lovecraft," writes historian David Skal, "the twenties didn’t roar; they dripped and festered and screamed."

eader of manuscripts. With Wright, a tall, gaunt man afflicted with Parkinson’s Disease, Weird Tales found its cloven hoofs, and The Unique Magazine began to publish some of the finest, and strangest, fiction ever marketed to a popular audience. The time was the mid-1920s, and Weird Tales’ cadre of poets and authors, led--artistically at least--by Lovecraft, told of a dark, surreal world of cyclopean horror which ran anathema to the Jazz Age of gin, speakeasies, and beautiful flapper girls. "For Lovecraft," writes historian David Skal, "the twenties didn’t roar; they dripped and festered and screamed."

Though he is chiefly responsible for creating the Weird Tales which is today remembered as a literary cauldron of surreal poetic vision, Wright has received a fair share of criticism for rejecting some classic works of fiction. He would often return stories for nebulous reasons, only to ask for their resubmission later on. Most notably, Wright rejected several of Lovecraft’s finest tales, feeding the author’s depression over his writing career and driving him to virtually abandon original works of fiction in the last years of his life. Ironically, when Lovecraft’s reputation soared following his death in 1937, readers forced Weird Tales to buy and publish every existing piece of Lovecraft’s fiction.

Still, it cannot be denied that Weird Tales under Wright’s editorship achieved a pinnacle of literary quality, introducing the world to a coterie of the finest craftsmen of the bizarre. Writers published during Wright’s reign include Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Howard, Robert Bloch, Manly Wade Wellman, Donald Wandrei, and even Tennessee Williams, whose  "The Vengeance of Nitocris" marked the Pulitzer-Prize-winning playwright’s first appearance in print.

"The Vengeance of Nitocris" marked the Pulitzer-Prize-winning playwright’s first appearance in print.

Decline

Weird Tales’ unique literary quality could not sustain it financially, however, and the pulp was beset with money woes throughout its troubled life. Wright’s health was steadily declining, and he was replaced in April 1940 with Dorothy McIlwraith. He died a few months afterwards.

Though generally regarded as a capable editor, McIlwraith lacked Wright’s vision. In addition, she was forced to contend with a drastically slashed budget and could not afford much of the quality material she desired to publish. Most of the authors from Weird Tales’ golden age had either died or moved on to better-paying work, and McIlwraith was forced to rely on second-generation writers and reprints from the old days.

Still, the later Weird Tales issues were not entirely devoid of groundbreaking literature. Under McIlwraith’s editorship, Weird Tales published stories by then-unknowns such as Ray Bradbury, Fritz Leiber, Richard Matheson, Theodore Sturgeon, and Joseph Payne Brennan.

McIlwraith was unable to save Weird Tales from its creditors, however, and the magazine breathed its last in September, 1954.

The Lamps Expire

Today, Weird Tales exists only as ephemera, forgotten almost entirely save by a few archivists and collectors. All told, only a small fraction of stories from its 279 issues have been reprinted, leaving the dreams of its dark princes crumbling along with the cheap pulpwood paper upon which they are printed. Few copies of the magazine survive; indeed it is rumored that only a dozen or so complete sets of Weird Tales exist. Libraries at the time of its publication failed to recognize the literary importance of the pulp, and ignored it almost entirely (in fact, one of the only library collections of Weird Tales is H.P. Lovecraft’s own—now housed in Brown University’s H.P. Lovecraft Collection and archived among the author’s papers and manuscripts). And with the passing of every year, more and more copies crumble away. The magazine was produced so cheaply, like all pulps of the time, that even with the finest of care, it is only a matter of time before nothing remains of Weird Tales but its legend, a myth itself, much like those it helped create.

Pulp paper gives off a certain scent as it decays - like cinnamon and sandalwood. It is the smell of dreams turning to dust.

© Lars Klores

© Lars Klores

for his terrific

Weird Tales site

(with permission)